When developers talk, they talk about stories, sprints, and releases. At the same time, finance talks about costs, assets, and how money is spread out over time. This mismatch causes confusion when someone asks whether a project can be treated as an asset, how much the company is really spending on the product, or why burn looks high even though the work adds long-term value.

The fix to this conundrum is software capitalization: instead of charging every coding cost to this month’s budget, you record some costs as assets and spread them over several years. However, the rules for this process can be tricky, and the whole thing can feel like busywork rather than help.

This guide breaks down the meaning of software capitalization, which costs qualify, how to run the process, and how to keep engineers and finance on the same page without needing to turn developers into accountants.

What Is Software Capitalization?

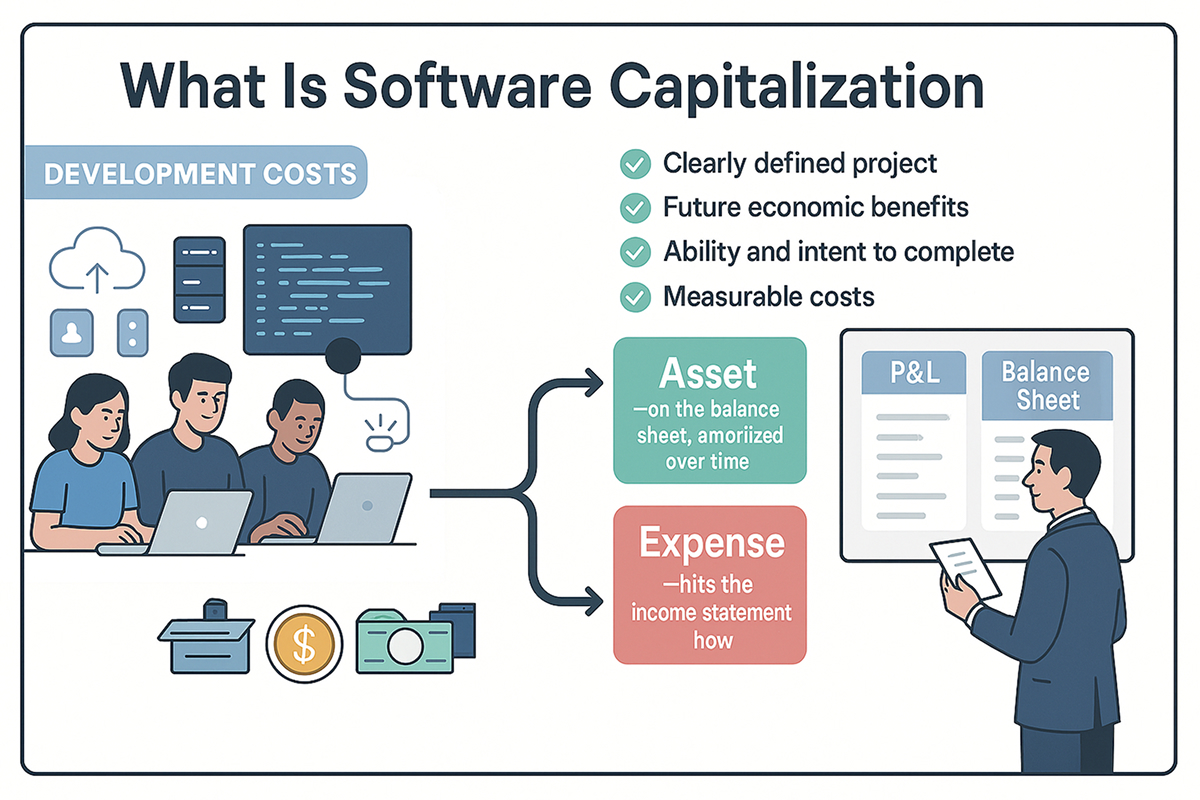

Software capitalization is the practice of treating certain development costs as long-term assets rather than current expenses. To understand this, it’s important to know the difference between an expense and an asset:

- Expense: Included in the income statement now.

- Asset: Lives on the balance sheet, then gets amortized over its useful life.

Accounting frameworks (such as US GAAP and IFRS) allow this, but only under certain conditions. In simple terms, you need to show that:

- There is a clearly defined project.

- The software will likely bring future economic benefits.

- You have the ability and intent to complete it.

- You can reliably measure the cost.

This is where engineering matters; finance can’t judge those points on its own. They need the developers’ view on what’s being built, when, and by whom.

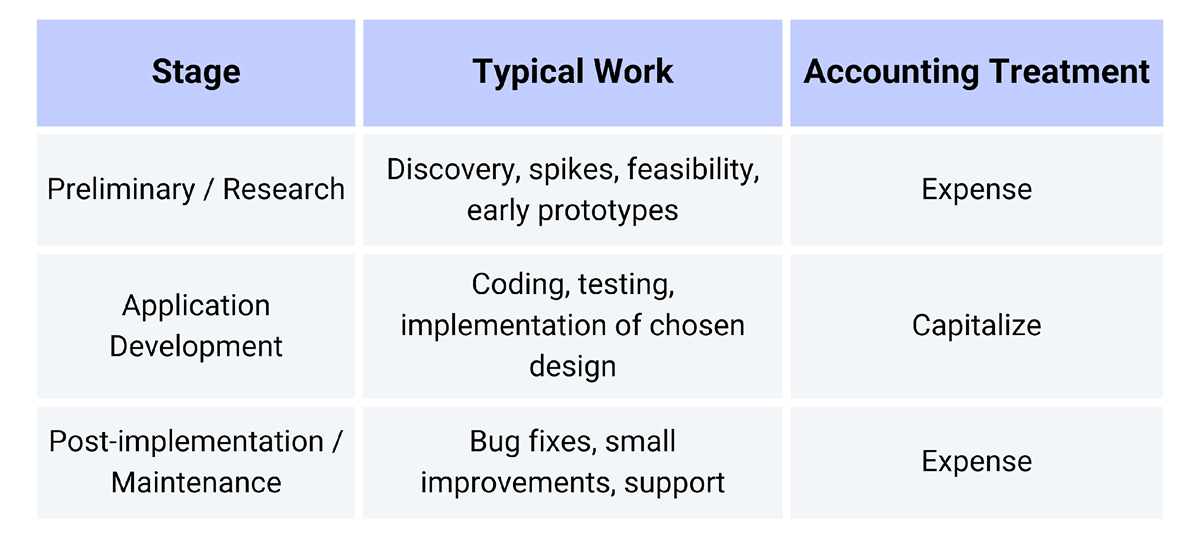

The Three Project Stages: When You Can (and Can’t) Capitalize

Most capitalization policies use a three-stage model.

1. Preliminary / Research (Always Expensed)

This is the “Are we even going to build this?” phase.

Examples:

- Market and user research

- High-level architecture options

- Spike tickets and throwaway prototypes

- Comparing platforms and vendors

Even if this work leads directly to a successful product, it’s still treated as an expense. The project is too uncertain at this stage.

2. Application Development (Capitalizable)

Once you commit to a specific product or feature set and start building it, you enter the development stage. This is where capitalization of software costs becomes possible.

Typical capitalizable items:

- Salaries and benefits for engineers working on the defined project

- Contractor fees for work directly tied to development or implementation

- Environment costs (e.g., cloud or test environments) dedicated to that project

- Specialized tools or licenses used mainly for that project

The key idea: These costs are for directly creating the software asset, not just exploring possibilities.

3. Post-Implementation / Maintenance (Expensed Again)

After launch, most work is no longer building a new asset. It’s maintaining or lightly enhancing the existing one.

Examples:

- Routine bug fixes

- On-call and incident response

- Minor enhancements or UX polish

- Regular performance tuning

These are expensed, unless you spin up a new, clearly defined project (e.g., “New Billing Engine v2”) that itself qualifies as a capitalizable development project.

Costs That Usually Don’t Qualify

Even during development, some costs usually are not capitalized:

- Training (internal or external)

- General management and administrative overhead

- Sales and marketing activities

- Company-wide tools and infrastructure not tied to a specific capitalized project

They might be essential for success, but they don’t meet the criteria for capitalization.

A Practical 7-Step Framework for Tech Teams

Let’s turn this into something you can actually run in a modern product and engineering organization.

Step 1: Write a Simple Capitalization Policy

Start with a short document (2–3 pages) that:

- Names the standard you follow (e.g., GAAP/IFRS)

- Defines the three stages and their treatment

- Describes what counts as a project

- Lists eligible activities and roles

- Explains the documentation you expect (e.g., tickets, time tracking, approvals)

Engineers should be able to read this without needing a dictionary. If the policy is unreadable, it won’t be followed.

Step 2: Define Project Boundaries Clearly

Capitalization happens per project, so you must know what’s inside the box.

For each capitalized project, document the:

- Project name and one-line description

- Start date (i.e., when you leave research and start committed development)

- Expected go-live date

- Main features or modules covered

- Teams or squads involved

This helps avoid the “everything in repo X is capitalized” problem. That’s a red flag for auditors.

Step 3: Map Engineering Activities to Categories

Connect real engineering work to the accounting model using simple categories in your issue tracker:

- Research/spikes

- Design/architecture

- Implementation/coding

- Testing/QA

- Documentation

- Maintenance/support

Then agree with finance on which combinations are capitalizable in the development stage (e.g., implementation, testing, and project-specific docs) and which are always expensed (i.e., research and support).

You don’t need to tag every commit. Just make sure your categories are consistent and understandable.

Step 4: Track Effort Without Killing Productivity

You need a reasonable way to estimate the developer time spent on each capitalized project.

Common options:

- Time tracking: Log hours by project and category. While very accurate, this is not always loved.

- Sprint-based allocation: For example, “Team A spent 70% of this sprint on Project Phoenix and 30% on support”.

- Story-point/capacity models: Use historical data to map points or tickets to effort and allocate costs proportionally.

Whichever you choose, keep it lightweight. People will not maintain a system that feels like a second job.

Step 5: Allocate Real Costs to Projects

Once you know the effort split, convert it into actual money:

- Employees: fully loaded cost (salary + benefits + taxes) × percentage of time on each project

- Contractors: invoice amounts tagged to projects or work packages

- Cloud and tools: cost allocation based on tags or dedicated environments

You don’t need perfect tags on day one. Start with rough but honest allocations, then refine. The important thing is that your method is consistent and defensible.

Step 6: Review Monthly with Finance

A monthly sync between engineering and finance avoids surprises.

Discuss:

- Which projects are in development, and which have moved to post-implementation

- Any major refactors or rewrites

- Big spikes that should remain expensed even if they live in the same repo

- Changes to team allocations (for example, a squad moved to a new initiative)

This is also the right place to challenge borderline cases. If everything is capitalized, something’s wrong. If nothing is, you may be missing legitimate assets.

Step 7: Handle Go-Live and Amortization

When a project goes live:

- Capitalization stops for that initial version.

- The total capitalized cost is recognized as an intangible asset.

- Finance chooses an amortization period (for example, 3–5 years).

- Each month, a small portion of that asset is expensed through amortization.

Engineering input is needed for:

- Estimating a realistic, useful life

- Signaling when software is obsolete or replaced (which may trigger impairment)

You don’t need to manage the journals, but your roadmap and deprecation decisions affect the numbers.

Tools and Documentation You Actually Need

You don’t need a new ERP system to start, but you do need a minimum set of building blocks, including:

- Work tracker: Jira, Linear, etc., with projects and labels that match your policy

- Effort tracking model: Time logs or sprint-based allocations

- Cost data: HR/payroll for employees, vendor systems for contractors, and cloud

- Capitalization policy: Accessible to engineering, not just buried in finance folders

- Audit trail: Project docs, architecture decisions, release notes, and monthly review notes

If you already have regular engineering-finance check-ins, you can plug capitalization into those. If not, this is a good reason to start.

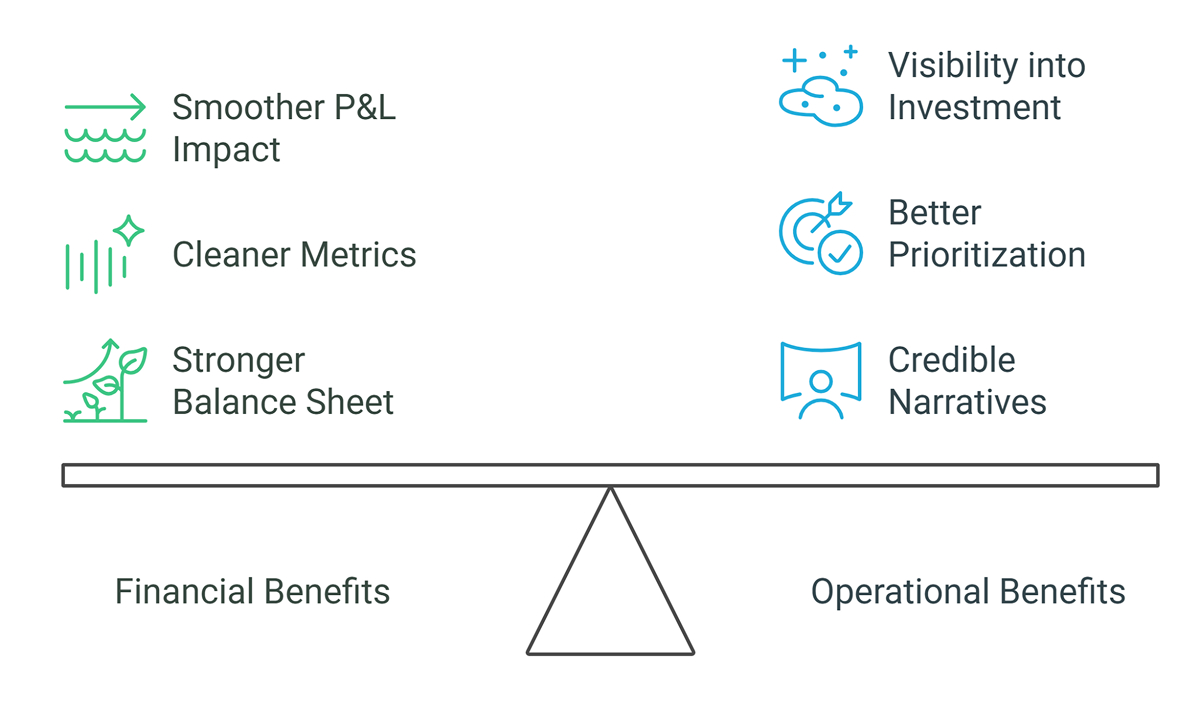

Benefits of Capitalizing Software Development Costs

Why bother with all of this?

Financial Benefits

- Smoother P&L: Big investments don’t explode in a single quarter; they’re spread over several years.

- Cleaner metrics: EBITDA and other operating metrics become more meaningful during high-investment phases.

- Stronger balance sheet: Your software appears as an asset, which better reflects reality for product-led companies.

Operational and Strategic Benefits

- Visibility into product investment: You can see how much really went into Payments v2 vs. internal tools.

- Better prioritization: When costs are tied to projects, trade-offs between initiatives become clearer.

- More credible narratives: In board meetings or investor updates, you can tell a story grounded in both the roadmap and financials.

Risks and Common Pitfalls

Capitalization is powerful, but it can backfire.

Over-capitalizing

- Treating almost all engineering work as capitalizable

- Rolling maintenance and support into “new development”

- Hiding weak margins behind aggressive capitalization

This can lead to audit findings and future restatements. If you’re ever unsure, it’s safer to expense.

Under-capitalizing

- Expensing everything because this is too complicated

- Missing the chance to show investments properly

- Making your P&L look far worse than the underlying economics

Here, you’re losing legitimate value. Start with one or two obvious projects and grow from there.

Weak Documentation

- No clear project boundaries

- Inconsistent tagging of tickets or time

- Vague cost allocations with no written rationale

The fix is not heavy bureaucracy; it’s small, predictable habits, such as a one-page project summary, a simple rules doc, and regular check-ins.

FAQ

1. What qualifies as capitalizable software development costs?

Costs qualify when they are directly tied to building a specific software product or feature in the development phase, not in research or routine maintenance. In practice, this usually means developer and contractor effort, plus project-specific environments and tools that create or significantly improve the software.

2. How do accounting standards such as GAAP and IFRS treat software capitalization?

According to the GAAP and IFRS accounting standards, internally created software can be classified as an intangible asset as long as the project meets the conditions of there being feasibility, a potential intention to completion, likely benefits, and the costs to the project are measurable, once the software moves from a research to a developmental state.

Once the software is available for use, the capitalized cost is amortized over the determined useful life and is subject to impairment evaluations if usage decreases or the software becomes obsolete.

3. What data or tools are available or required to ensure correct software cost capitalization?

To support software cost capitalization, the software project should include a work tracker that provides an easy way to estimate or record effort to engineering and to access cost data for employees, contractors, and cloud tools. Other documents, such as project charters, architectural designs, and release records, can help explain what software was created, when it moved to a different stage, and the costs incurred at the time.

4. What could go wrong by misclassifying expenses related to developing software?

Overcapitalization can inflate asset values and short-term net income, thereby increasing the risk of audits and restatements. Undercapitalization can make periods of high spending look worse than they actually are and obscure how much money is really being lost on the products, which can confuse both internal and external stakeholders.

5. When should a company expense software costs rather than capitalize them?

When the work is exploratory research, routine maintenance, minor improvements, support, or any other activity that doesn’t clearly create or significantly upgrade a separate software asset, the cost of the software should be written off. Suppose the project is highly uncertain or the team cannot reliably measure effort and link it to a defined development phase; in that case, expensing is usually the safer and more defensible choice.

Conclusion

Capitalizing software development costs is not just an accounting trick. It’s a structured way to connect what engineering builds with how the company reports value.

When you (1) define clear stages and policies, (2) draw reasonable project boundaries, (3) track effort in a lightweight way, and (4) review assumptions regularly with finance, you get financials that better reflect reality, without drowning your teams in process.

You still ship code. You still care about uptime, quality, and developer happiness. But now, when someone asks, “Can we capitalize this project?” you can answer with confidence, using a framework that both engineering and finance can stand behind.